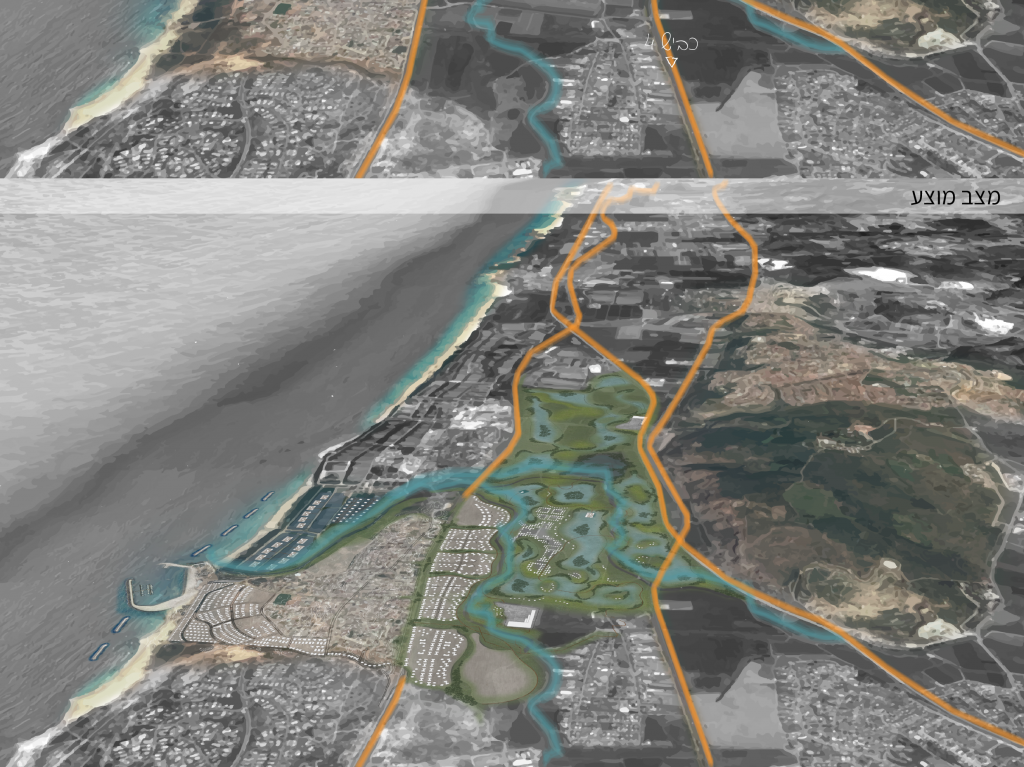

Jisr az-Zarqa: from the stream to the swamp, into the sea. The environment that surrounds Jisr az-Zarqa as a reinforcing factor

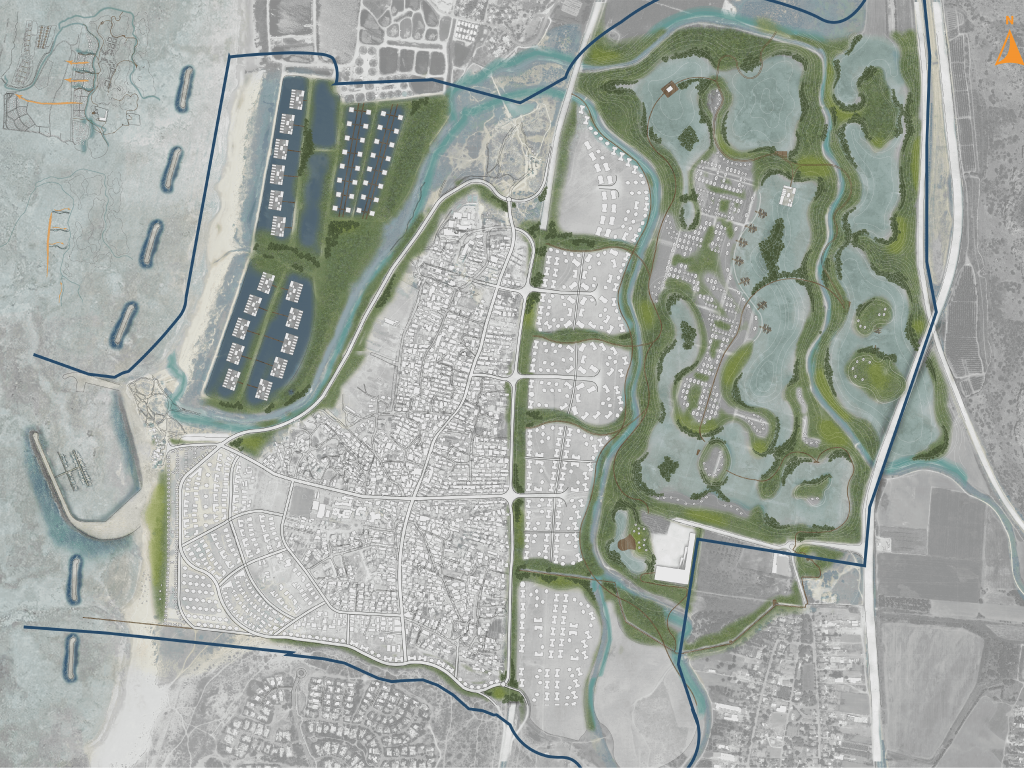

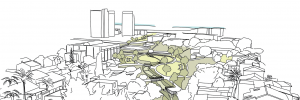

To the south of the confluence of Nahal Taninim and Nahal Ada, by the coast, along the Kurkar ridge and amidst a unique landscape, lies the town Jisr a-Zarqa, a locality of low socioeconomic status with a disadvantaged population. The town is bounded, unable to develop because of the restrictive environment surrounding it: Route 2 to the east, the beach to the west, fish ponds and a nature reserve to the north and a dike to the south. The restrictions placed on the locality have resulted in a high population density, lack of open spaces and new residential areas and, beyond that, detachment of the residents from their original environment. Such detachment from the environment has manifested in a loss of identity. A person who loses his identity becomes frustrated, and this frustration is expressed in anger and crime, leading to a situation such as the current one of Jisr az-Zarqa. The idea behind this project began with the assumption that landscape and environmental qualities are directly connected with quality of life. In other words, quality of life improves in accordance with the value of environment and landscape. Yet for various reasons this assumption does not apply to Jisr az-Zarqa. Such a situation is expressed as environmental injustice.

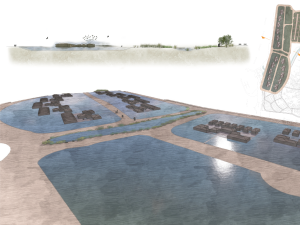

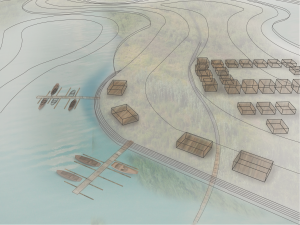

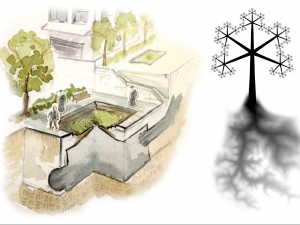

There are two components that can affect the equation of landscape and environmental qualities with the quality of life: residents and environment. In the past, the environment was an important ingredient in the lives of the residents of Jisr az-Zarqa, but it was a different environment, an aquatic environment with a unique landscape and ecological characteristics that could provide system services like food and shelter for its residents. The inhabitants, from the El-Ghaouarni tribe, a Bedouin tribe that roamed in Israel in the 19th century, settled mainly in swampy areas such as the Kabara swamps on the Carmel coast. The El-Ghaouarni tribe has a gene that distinguishes it – the sickle cell anemia gene – because of which tribe members can live in an aquatic environment without contracting Malaria, and this was their source of strength. The swamps, which had undergone significant changes since the Roman period, were drained and exploited in the early 20th century. As a result, the swamps that had been a habitat for its residents, El-Ghaouarni, and the ecosystems have disappeared. As compensation for these territories, the El-Ghaouarni tribe was transferred to Jisr az-Zarqa.

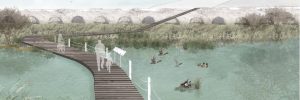

The project posits that from the moment the swamps were drained, Jisr az-Zarqa’s population has become increasingly disadvantaged. Therefore, the project suggests that some of the Kabara swamps be restored and designated as a habitat and a functioning ecosystem serving Jisr az-Zarqa residents. Thanks to the swamps, the area will have a new unique landscape that can serve the localities of the area in general and the residents of Jisr az-Zarqa in particular. These services would manifest as regulating services and cultural services. The project would create a new image that could promote various opportunities for the underprivileged population, restore its connection to its environment and allow it to recover.