Dar Abuna

I live with my family in a two-story private house, one floor above my grandparents and one floor below my soon-to-be-married brother’s house. This house is part of my extended family compound, which includes two other private houses for my uncles and is situated within a larger Hamula compound. After 25 years in this environment, I’ve gained insight into both its strengths and weaknesses.

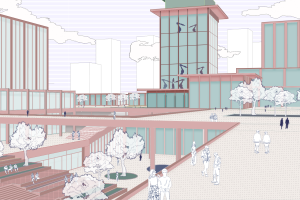

The project began as a critique of the current structural conditions of my family compound, leading to its reconstruction, hence the name Dar Abuna. “Dar Abuna” is an Arabic term translating to “our father’s house,” describing a place that embodies a sense of home and ownership. It signifies a comfort level that prompts individuals to treat the space as their own—where community members might even dance in the street because it feels like home.

Dar Abuna has evolved into a project aimed at developing a new urban planning strategy for Arab dwellings in Israel. Over the years, Arab housing has transitioned from traditional structures like houses and liwans to courtyard houses, each typology preserving qualities essential to Arab life. However, significant changes in Arab communities over recent decades have influenced the housing types in these settlements. As noted by Rassem Khamaisi (2013), they have shifted from small, traditional village-type communities to more modern, hybrid rural-urban “urbanized villages,” adapting to unique environmental circumstances.

Currently, self-built, privately financed houses dominate Arab settlements, leading to land consumption and reduced housing density. The Israeli Land Administration and Ministry of Housing often design urban plans that aim to increase the number of residences but fail to consider family dynamics and land division. Consequently, these plans face heavy criticism and are rarely implemented (Khamaisi, 2019).

Increasing density and land shortages have pushed many Arab residents to abandon traditional lifestyles, opting instead for rental apartments in standardized communal housing, distancing them from family connections. The construction conditions create numerous challenges, preventing further home expansion. Building restrictions limit lots to accommodate only two to three families, leaving unused spaces and unplanned houses, compounded by a lack of public services and unavoidable privacy accessibility issues.

However, the current housing typology has positive aspects worth preserving, such as proximity to family, intergenerational relationships within the Hamula, and the characteristics of private houses. As noted by Totry-Fakhoury & Alfasi (2018), while Palestinians desire to engage in the modern economy, there exists a fear of losing cultural values and assimilating into the colonial state. The growing density complicates the ability of Arab residents to maintain their quality of life.

Therefore, this project proposes a new strategy aimed at enhancing life within Hamulas and strengthening the bonds between younger and older generations in families. It will be grounded in fundamental research on Arab identity and lifestyle, aiming to retain the valued qualities of existing housing while addressing the outlined challenges.